News | March 5, 2014

Warm rivers play role in Arctic sea ice melt

A research team led by Son Nghiem of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., used satellite data to measure the surface temperature of the waters discharging from a Canadian river into the icy Beaufort Sea during the summer of 2012. They observed a sudden influx of warm river waters into the sea that rapidly warmed the surface layers of the ocean, enhancing the melting of sea ice. A paper describing the study is now published online in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

“River discharge is a key factor contributing to the high sensitivity of Arctic sea ice to climate change,” said Nghiem. “We found that rivers are effective conveyers of heat across immense watersheds in the Northern Hemisphere. These watersheds undergo continental warming in summertime, unleashing an enormous amount of energy into the Arctic Ocean, and enhancing sea ice melt. You don’t have this in Antarctica.”

The team said the impacts of these warm river waters are increasing due to three factors. First, the overall volume of water discharged from rivers into the Arctic Ocean has increased. Second, rivers are getting warmer as their watersheds (drainage basins) heat up. And third, Arctic sea ice cover is becoming thinner and more fragmented, making it more vulnerable to rapid melt. In addition, as river heating contributes to earlier and greater loss of the Arctic’s reflective sea ice cover in summer, the amount of solar heat absorbed into the ocean increases, causing even more sea ice to melt.

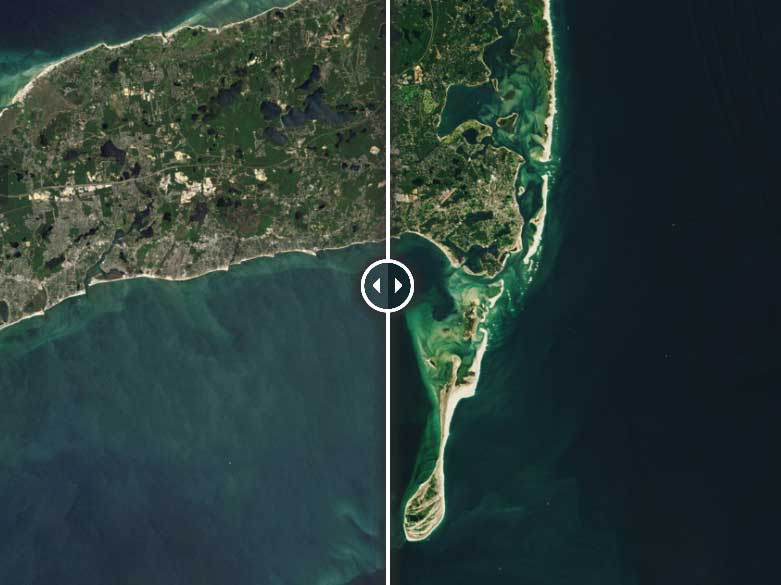

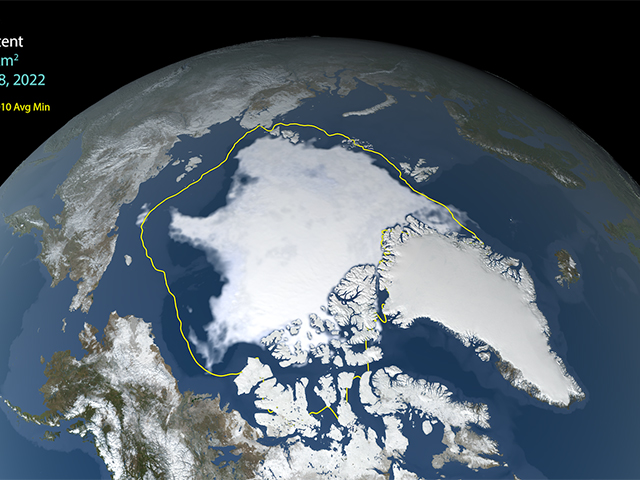

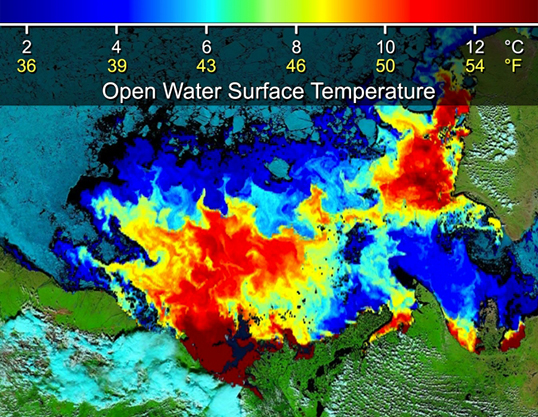

To demonstrate the extensive intrusion of warm Arctic river waters onto the Arctic sea surface, the team selected the Mackenzie River in western Canada. They chose the summer of 2012 because that year holds the record for the smallest total extent of sea ice measured across the Arctic in the more than 30 years that satellites have been making observations.

The researchers used data from satellite microwave sensors to examine the extent of sea ice in the study area from 1979 to 2012 and compared it to reports of Mackenzie River discharge. “Within this period, we found the record largest extent of open water in the Beaufort Sea occurred in 1998, which corresponds to the year of record high discharge from the river,” noted co-author Ignatius Rigor of the University of Washington in Seattle.

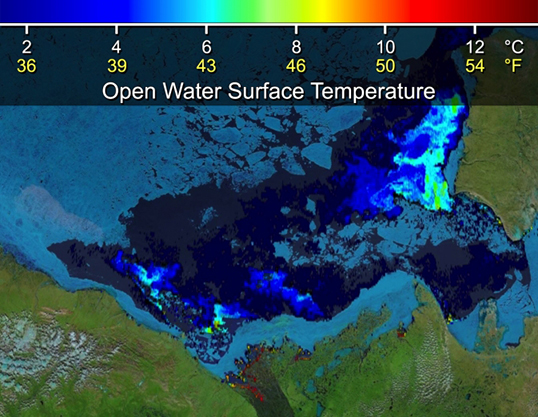

The team analyzed data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument on NASA’s Terra satellite to examine sea ice patterns and sea surface temperatures in the Beaufort Sea. They observed that on June 14, 2012, a stretch of landfast sea ice (sea ice that is stuck to the coastline) formed a barrier that held the river discharge close to its delta. After the river water broke through the ice barrier, sometime between June 14 and July 5, the team saw that the average surface temperature of the area of open water increased by 11.7 degrees Fahrenheit (6.5 degrees Celsius).

“When the Mackenzie River’s water is held back behind the sea ice barrier, it accumulates and gets warmer later in the summer,” said Nghiem. “So when it breaks through the barrier, it’s like a strong surge, unleashing warmer waters into the Arctic Ocean that are very effective at melting sea ice. Without this ice barrier, the warm river waters would trickle out little by little, and there would be more time for the heat to dissipate to the atmosphere and to the cooler, deeper ocean.”

“If you have an ice cube and drop a few water droplets on it, you’re not going to see rapid melt,” said co-author Dorothy Hall of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. “But if you pour a pitcher of warm water on the ice cube, it will appear to get smaller before your eyes. When warm river water surges onto sea ice, the ice melts rapidly.”

Nghiem’s team has linked this sea ice barrier, which forms recurrently and persistently in this area, to the physical characteristics of the shallow ocean continental shelf, and concludes the seafloor plays a role in delaying river discharge by holding the barrier in place along the shore of the Mackenzie delta.

The team estimated the heating power carried by the discharge of the 72 rivers in North America, Europe and Asia that flow into the Arctic Ocean. Based on published research of their average annual river discharge, and assuming an average summer river water temperature of around 41 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius), they calculated that the rivers are carrying as much heat into the Arctic Ocean each year as all of the electric energy used by the state of California in 50 years at today’s consumption rate.

While MODIS can accurately measure sea surface temperature where rivers discharge warm waters into the Arctic Ocean, researchers currently lack reliable field measurements of subsurface temperatures across the mouths of river channels. Nghiem said more studies are needed to establish water temperature readings in Arctic-draining rivers to further understand their contribution to sea ice melt.

Learn more about NASA’s Earth science activities in 2014.

Learn about NASA's latest Earth science findings.