News | August 17, 2014

New satellite data will help farmers facing drought

For several months, California has been in a state of “exceptional drought.” The state’s usually verdant Central Valley produces one-sixth of the U.S.’s crops. Credit: White House via Wikimedia Commons

About 60 percent of California is experiencing “exceptional drought,” the U.S. Drought Monitor’s most dire classification. The agency issued the same warning to Texas and the southeastern United States in 2012. California’s last two winters have been among the driest since records began in 1879. Without enough water in the soil, seeds can’t sprout roots, leaves can’t perform photosynthesis, and agriculture can’t be sustained.

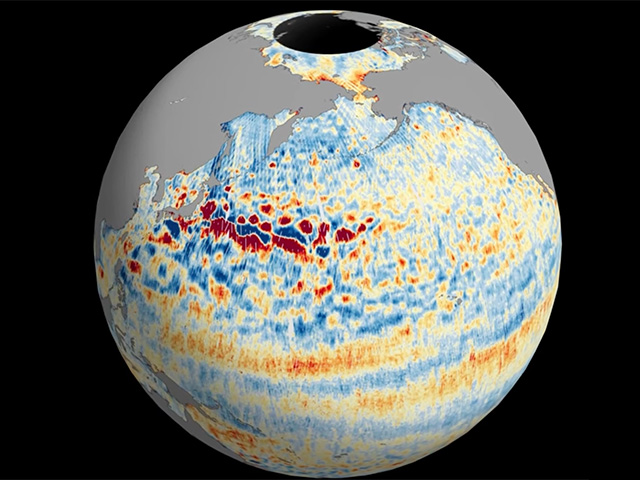

Currently, there is no ground- or satellite-based global network monitoring soil moisture at a local level. Farmers, scientists and resource managers can place sensors in the ground, but these only provide spot measurements and are rare across some critical agricultural areas in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The European Space Agency’s Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity mission measures soil moisture at a resolution of 31 miles (50 kilometers), but because soil moisture can vary on a much smaller scale, its data are most useful in broad forecasts.

Enter NASA’s Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) satellite. The mission, scheduled to launch this winter, will collect the kind of local data agricultural and water managers worldwide need.

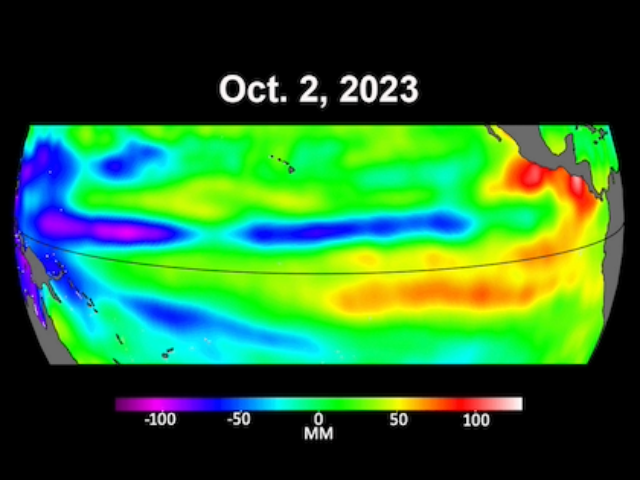

SMAP uses two microwave instruments to monitor the top 2 inches (5 centimeters) of soil on Earth’s surface. Together, the instruments create soil moisture estimates with a resolution of about 6 miles (9 kilometers), mapping the entire globe every two or three days. Although this resolution cannot show how soil moisture might vary within a single field, it will give the most detailed maps yet made.

“Agricultural drought occurs when the demand for water for crop production exceeds available water supplies from precipitation, surface water and sustainable withdrawals from groundwater,” said Forrest Melton, a research scientist in the Ecological Forecasting Lab at NASA Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California.

“Based on snowpack and precipitation data in California, by March we had a pretty good idea that by summer we’d be in a severe agricultural drought,” Melton added. “But irrigation in parts of India, the Middle East and other regions relies heavily on the pumping of groundwater during some or all of the year.” Underground water resources are hard to estimate, so farmers who rely on groundwater have fewer indicators of approaching shortfalls than those whose irrigation comes partially from rain or snowmelt. For these parts of the world where farmers have little data available to help them understand current conditions, SMAP's measurements could fill a significant void.

Some farmers handle drought by changing irrigation patterns. Others delay planting or harvesting to give plants their best shot at success. Currently, schedule modifications are based mostly on growers’ observations and experience. SMAP’s data will provide an objective assessment of soil moisture to help with their management strategy.

“If farmers of rain-fed crops know soil moisture, they can schedule their planting to maximize crop yield,” said Narendra Das, a water and carbon cycle scientist on SMAP’s science team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “SMAP can assist in predicting how dramatic drought will be, and then its data can help farmers plan their recovery from drought.”

“Scientists see tremendous potential in SMAP,” Melton said. “It is not going to provide field-level information, but it will give very useful new regional observations of soil moisture conditions, which will be important for drought monitoring and a wide range of applications related to agriculture. Having the ability provided by SMAP to continuously map soil moisture conditions over large areas will be a major advance.”