News | September 21, 2015

The hidden meltdown of Greenland

And … it’s melting.

In August 2014, Eric Rignot, a glaciologist working at the University of California, Irvine and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, led a team in mapping ice cliffs at the front edges of three outlet glaciers in Greenland. The researchers found cavities that undercut the base of these leading edges that can destabilize the ice front and enhance iceberg calving, the process where parts of the glacier break off and float away.

"In Greenland we have melt rates of a few meters a day in the summer months," says Rignot.

What’s causing this "big thaw"?

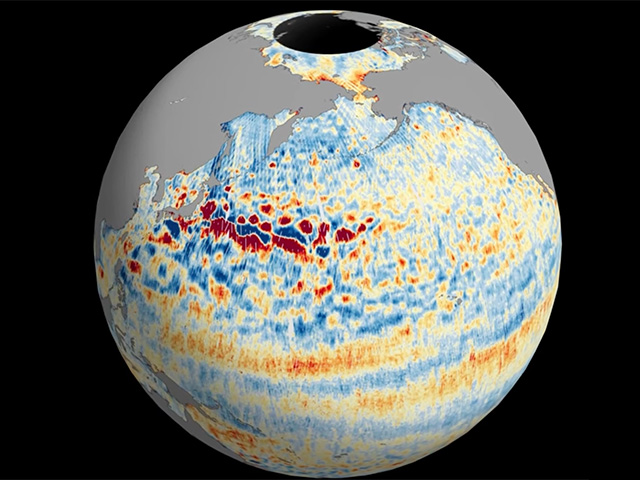

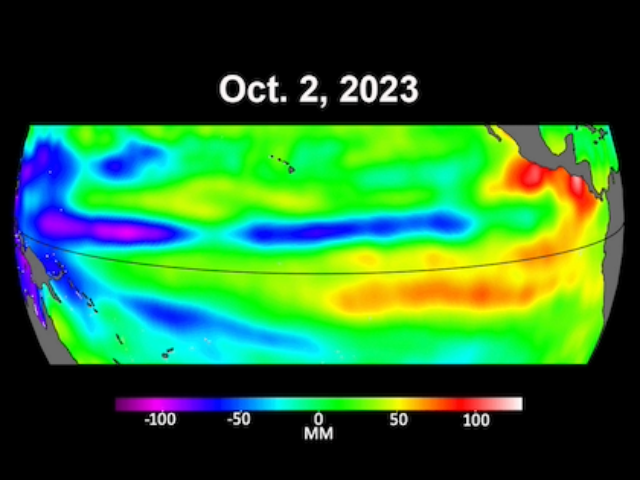

Rignot’s team found that Greenland's glaciers flowing into the ocean are grounded deeper below sea level than previously measured. This means that the warm ocean currents at depth can sweep across the glacier faces and erode them.

"In polar regions, the upper layers of ocean water are cold and fresh,” he explains. "Cold water is less effective at melting ice."

"The real ocean heat is at a depth of 350-400 meters and below. This warm, salty water is of subtropical origin and melts the ice much more rapidly."

Rignot’s research team is providing critical information needed to document this effect and accurately predict where and how fast glaciers will give way. The team gathered and analyzed around-the-clock measurements of the depth, salinity and temperature of channel waters and their intersection with the coastal edge of Greenland's ice sheet.

They found that some of the glaciers balance on giant earthen sills that are protecting them, for now. But other glaciers are being severely undercut out of sight beneath the surface, meaning they could collapse and melt much sooner.

It’s not easy gathering such data. On top of the rough waters, wind, rain and cold weather, there’s the ice itself.

"We came to study glaciers that discharge into the fjord. And the fjords are full of ice. In some places it can be so full of ice that the boat can’t even push through."

But ice holds a peculiar fascination for Rignot. "I’ve always been interested in polar regions," he says. "My friends wanted to cruise in the Caribbean but I’d rather cruise here in these waters. I don’t know why. I just like them."

What’s next?

"OMG," answers Rignot. And he’s not using chatspeak.

OMG stands for Ocean Melting Greenland — the name of a new NASA-funded 5-year project that will take their investigation even further, to the four corners of Greenland by ship and by plane.

"We hope that the data collected will be a game changer for studying ice-ocean interaction in Greenland," says Rignot. "It will help modelers make better projections of Greenland ice sheet melt in the future."

Rignot’s results have been accepted for publication in the journal Geophysical Research Letters and are now available online.