News | November 14, 2016

Extremely warm 2015-'16 winter cyclone weakened Arctic sea ice pack

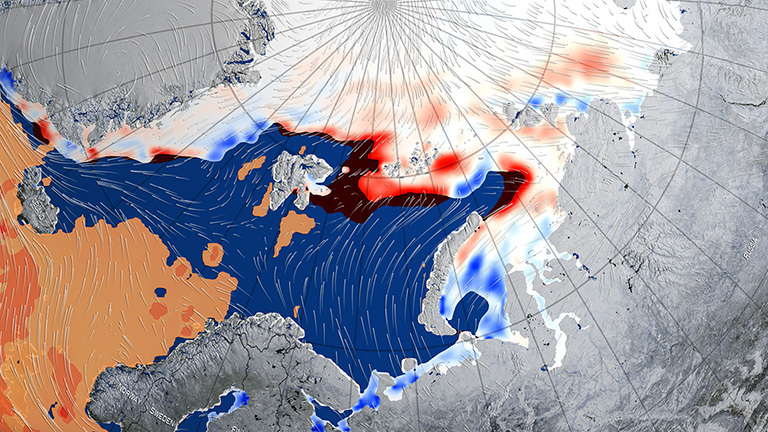

This image shows the winds and warm mass of air associated with a large cyclone that swept the Arctic in late December 2015-early January 2016, thinning and shrinking the sea ice cover. Credit: NASA Goddard's Scientific Visualization Studio/Alex Kekesi, data visualizer.

A large cyclone that crossed the Arctic in December 2015 brought so much heat and humidity to this otherwise frigid and dry environment that it thinned and shrank the sea ice cover during a time of the year when the ice should have been growing thicker and stronger, a NASA study found.

The cyclone formed on Dec. 28, 2015, in the middle of the North Atlantic, and traveled to the United Kingdom and Iceland before entering the Arctic on Dec. 30, lingering in the area for several days. During the height of the storm, the mean air temperatures in the Kara and Barents seas region, north of Russia and Norway, were 18 degrees Fahrenheit (10 degrees Celsius) warmer than what the average had been for this time of the year since 2003.

The extremely warm and humid air mass associated with the cyclone caused an amount of energy equivalent to the power used in one year by half a million American homes to be transferred from the atmosphere to the surface of the sea ice in the Kara-Barents region. As a result, the area’s sea ice thinned by almost 4 inches (10 centimeters) on average.

At the same time, the storm winds pushed the edges of the sea ice north, compacting the ice pack.

“During the cyclone, the sea ice retreated northward, causing a loss in coverage equaling the area of the state of Florida,” said Linette Boisvert, lead author of the study and a sea ice scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Boisvert and her colleagues used data from NASA’s Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument aboard the Aqua satellite to study the atmospheric effects of this storm on the sea ice, specifically the evolution of air temperature and humidity during the storm. They also compared the cyclone to other extreme events from past winters since 2003, the year AIRS began to collect data.

“Measured against other extreme winter events that have happened in the Kara-Barents seas region over the AIRS period, this one was the warmest,” Boisvert said. “The AIRS time period also coincides with the warmest decade on record, so this storm being the hottest is a big deal.”

The researchers also used a reanalysis of wind speeds, satellite passive microwave data of Arctic sea ice concentration and a sea ice thickness model to study how the storm impacted the sea ice cover.

Usually, during the Arctic winter the atmosphere and surface of the ice are very cold, while the exposed ocean waters are warmer, so there’s a heat transfer from the ocean to atmosphere. During the cyclone, the pattern was inverted and heat traveled from the atmosphere to the surface of the ice. After the storm, the weather in the Kara-Barents seas region remained warmer than average for January, leading scientists to believe this cyclone prevented the sea ice from recovering.

During the months of January, February and March of this year, Arctic sea ice presented the lowest monthly extents in the satellite record, which were largely driven by abnormally low ice levels in the Kara and Barents seas.

Model projections of Arctic sea ice show that ice thickness will continue to decline over the next decades, making the sea ice cover even more vulnerable to winter storms.

“In our study, we found that the thinnest ice was completely melted out by the storm,” said Alek Petty, a co-author of the study and a sea ice researcher at Goddard. “Maybe in the coming years, if we start with a thinner winter ice pack we’ll see extreme events like these cause even bigger melt-outs across the Arctic.”